Visiting vineyards and talking with wine growers helps bridge the knowledge gap between wine and the vine

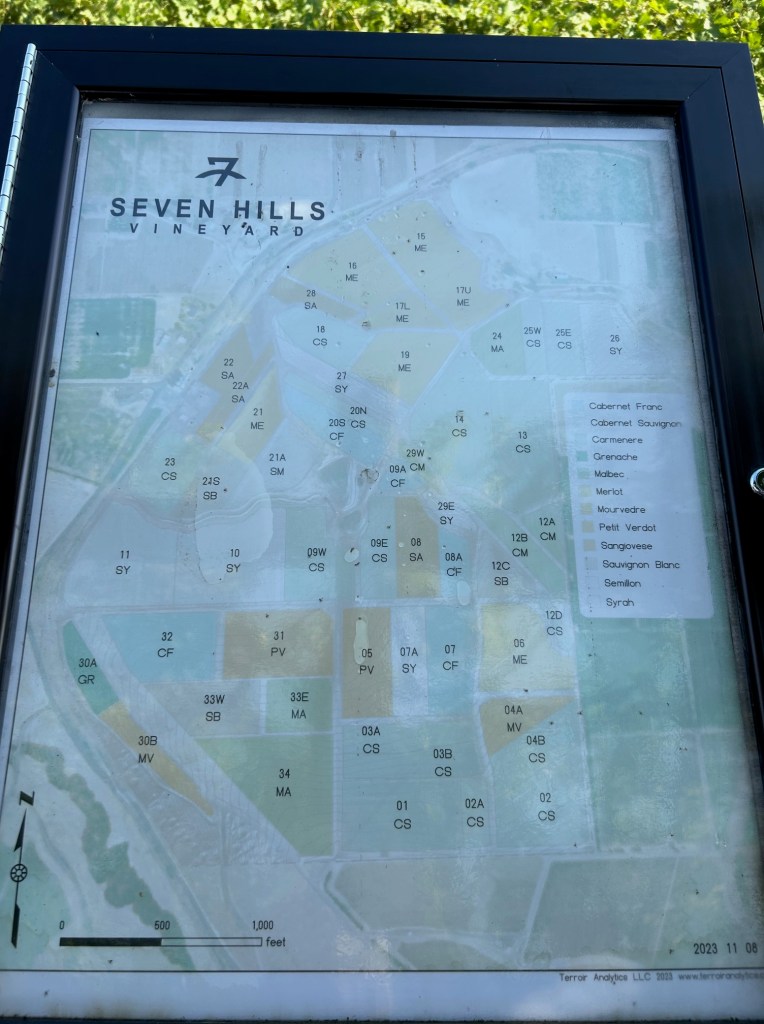

Seven Hills vineyard, directly behind the gazebo.

One of the best ways to learn about wine, or any subject, is to form a personal relationship with it. It’s much easier to retain information, take an interest in something, and expand your knowledge if you actually feel invested in or somehow connected to the topic. (Sorry, math, you really never stood a chance…)

It has been a real education moving from a large, wine-loving city (Seattle) to a much smaller wine-producing region (Walla Walla). Once I grasped the basic lay of the land in my new hometown, I began to realize there was a huge gulf in my understanding of wine as I knew it—mainly, a consumer product—and the actual process of grape growing and winemaking, from who’s-who and what’s-where in a still-growing local industry of over 130 wineries, to being able to identify notable vineyards on a map.

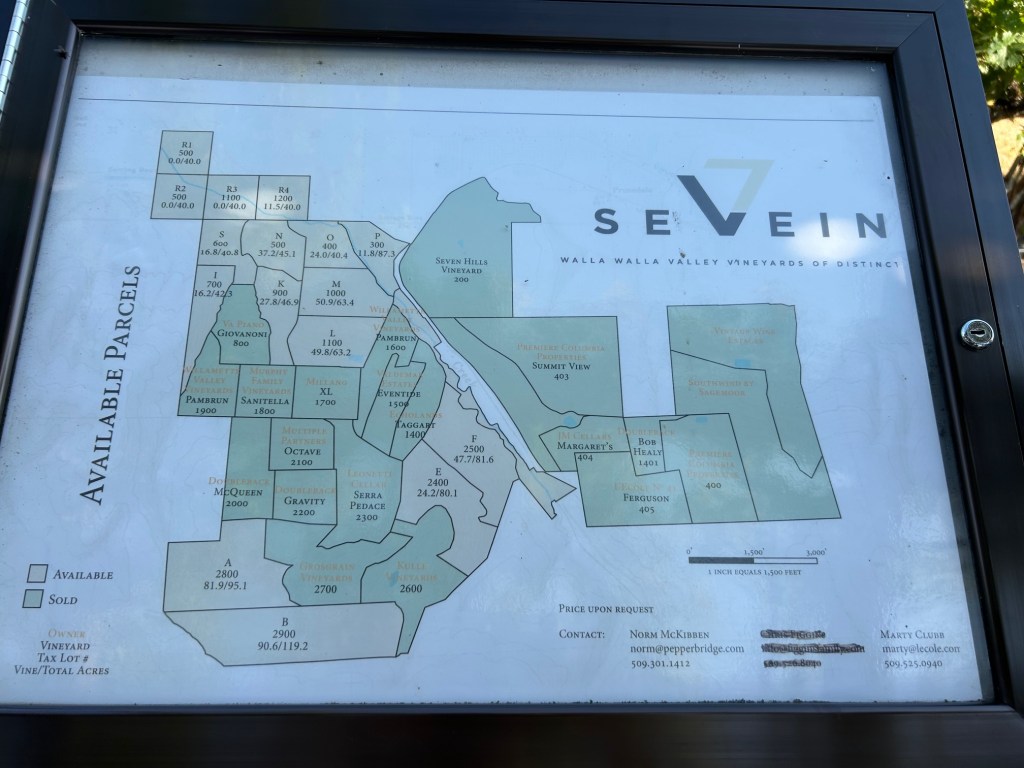

For perspective and a general orientation, it’s helpful to plant boots on the ground whenever the opportunity presents itself, so I eagerly accepted an invitation from the Walla Walla Valley Wine Alliance to visit SeVein vineyards on a warm early August morning with other members of the local wine industry.

The first thing that occurred to me as I carpooled over with my Pursued by Bear colleagues Stacie Pike and Marshall Dunovant, is that rural Milton-Freewater is surprisingly…pretty. The town’s dismal main drag, checkered with shuttered businesses, graffiti, and discount stores, makes a sad first impression, but just a few miles west is quintessential wine country, with gnarled vines, sun-scorched trees, abundant orchards, quaint country houses, and views in every direction.

(As I was telling my husband Toby about my day, he said, “You know what they say: Grapes love a good view! I learned that from the Bible.”

I shot him a puzzled look. We are typical agnostic ex-Seattleites.

“The Wine Bible, Gwen!”)

Anyway….

This particular location in Milton-Freewater is distinct from the area’s famous Rocks District, which, as the Oregon Wine Board explains, comprises “a very gently sloping alluvial fan that was deposited by the Walla Walla River where it exits the foothills of the Blue Mountains and enters the broad flat floor of the Walla Walla Valley [with elevations from 800 to 1,000 feet].”

Our destination was mostly wind-blown glacial loess (silty soils) over fractured basalt, on a slope that tops out at 1450 feet. (I’m obviously not a geologist, but Rocks and SeVein soils are different. One very crude way to think about this is that in the Rocks, the basalt is mostly on the top of the soil—these rocks are the football-sized cobblestones you can very easily see among the vine rows. At SeVein, the basalt is under the topsoil (you can’t see it), often erratically situated, and from depths of two to over 15 feet below the ground surface.)

Eventually the scenery gave way to more and more plots of tidy, orderly vineyards until we entered a sprawling complex of them—SeVein Vineyards, “a collection of some of the most technologically advanced vineyard properties in the Walla Walla Valley,” according to the website. (The site is 2700 acres, with 1800 acres allocated to growing grapes, and 1000 acres currently planted to them.)

On a dry grass road winding through blocks of syrah and other grape varieties, we made our way to about 1050 feet and stopped at a shaded gazebo covered with baco noir grapevines. It overlooked Seven Hills vineyard, first planted in 1980 and one of the founding vineyards in the appellation. The site has grown over the years to more than 200 acres, and approximately 50 winery clients source fruit from it, according to its website.

We met Monique Ortiz there, a viticulturist who works at the vineyard for North Slope Management, the site’s in-house group of expert grape growers. I happily recalled first encountering Ortiz (who has an effervescent and engaging personality) at a “Women on the Rise Event” a few years ago at the Walla Walla Community College.

Since then, Ortiz won the Washington Wine Industry Foundation’s Bill Powers Sabbatical award and traveled to Spain to enhance her knowledge of viticulture. I enjoyed reading about her trip here and made a note to ask her for an interview sometime before my fellowship period expires.

Ortiz talked about the site’s history and elevation (some of which can be found here), and spoke of the challenges of grape growing, and Seven Hills’ commitment to sustainable stewardship. I enjoyed learning about the mustard, arugula, and vetch cover crops that are planted to help manage nematodes (a type of parasitic worm) that feed on vine roots. It’s funny to think that the worms don’t like spicy food…

We continued uphill and visited XL (that’s the Roman numeral for 40, as in acres, the size of the vineyard—not a reference to the Hanes t-shirt size) next, at 1325 feet. Nick Mackay, Director of Vineyard Operations, Columbia Valley, for Results Partners met us there.

Mackay spoke of challenges on his parcel, too, namely, the discovery of another dreaded insect: phylloxera, that he said gave the vineyard “a bad name,” even though the pest has now been found widely across Walla Walla (and some assume other parts of Washington state) and is being successfully managed. And a hard freeze in January that led to 100% bud damage in some areas of the vineyard.

Still, Mackay said such pressures are not unique to Walla Walla, and that every growing region has its own set of challenges, whether it’s scarcity of water, extreme temperatures, or wildfire smoke.

If there is a key to success in winegrowing, Mackay says it lies in diversity: Winery clients would be wise to reduce their overall risk investing in more properties (as opposed to one, or just a few) and that diversity—from a range of elevation to soil types and conditions to microclimates—is one of the Walla Walla valley’s strengths.

Because of the diversity to be found here, he said, “there’s going to be some deals coming up from California,” a trend Washington wine country is already starting to see. Mackay encouraged attendees to emphasize this differentiating aspect when communicating winegrowing information to guests in the tasting room.

We concluded our visit a few parcels over at Sanitella Vineyard, the estate vineyard for Caprio Cellars. Planted mostly to cabernet and at roughly the same elevation as XL, Chris Banek of Banek Vineyard Management talked passionately about the people of wine, the things he’s learned from “badass winemakers,” his dependence on migrant labor, and how the team dynamic of “people who are really into it” makes the endeavor worthwhile.

His unique challenge at Sanitella, he said, was “nutrition”—that perfect combination of nutrients and fertilizers needed to help grape vines thrive—and this includes his efforts to reduce pesticide applications as much as possible, and how to manage pH levels in well water that get higher the further down water is derived (which is a real concern, as drought conditions persist). He talked a lot about learning from the data and updates provided by ongoing chemical analysis and lab work that helps inform his decisions.

It was refreshing to hear Banek’s grounded, practical views on grape growing and his keen awareness that the land does not farm itself. There is a relationship between the land and people at all levels of winemaking that must be recognized and respected.

Tracy Parmer of the Alliance asked about any misconceptions consumers might have about wine growing, and he said it was ignorance of the blood, sweat, and tears that goes into keeping a vineyard productive. Consumers might have a romantic idea that happy workers go around lazily picking grapes in beautiful settings, but the reality is much gritter, more calculated, more dependent on market forces, the weather, and entirely more exasperating.

On that note, we wrapped the day with lunch courtesy of the Alliance (provided by The Mill) at Northstar winery, complete with a refreshing glass of Merlot rosé. My salad came with a side of chicken, which I gave to Marshall, and Stacie and I traded chips (her salt and vinegar for my barbecue).

I texted a picture of the three of us to our boss, Kyle MacLachlan.

“Beautiful…and looks warm!” he replied.

As the mercury approached 102, it was indeed.

It was also a day to invest more in my personal relationship with wine, connect further with my new community, and strengthen my knowledge in a more holistic way.

We’ll see where this goes!

Previous Post: I Won a Fellowship

Leave a comment