As fall arrives, I’m taking stock of summer’s rush of activities, and looking ahead to a slower season with a few strategic trips on the calendar.

My vineyard visits and meetings with winemakers and vineyard managers begin October 21st, and I’m excited for a packed itinerary that will take me to many of the state’s renowned growing regions and appellations. (I’ll be blogging about it!)

I’m particularly excited about the agenda’s focus on many of the state’s sustainably-certified vineyards to learn more about the new Sustainable WA vineyard certification program and its practical applications in the field (and in the bottle).

Then in November, Toby and I head to Portland for a visit with his family and from there we fly to D.C. to catch up with my sister, her family, and my mom and dad who will be driving up from the Finger Lakes. I’ve been reading more about the rise of wine from Virginia and wanted to book some tastings, but most of the wineries are too far away for a day trip with a caravan three generations full, so Toby and I will be scouting for a local tasting room instead.

Speaking of reading, I’ve been reading through a stack of titles and writing on a range of topics.

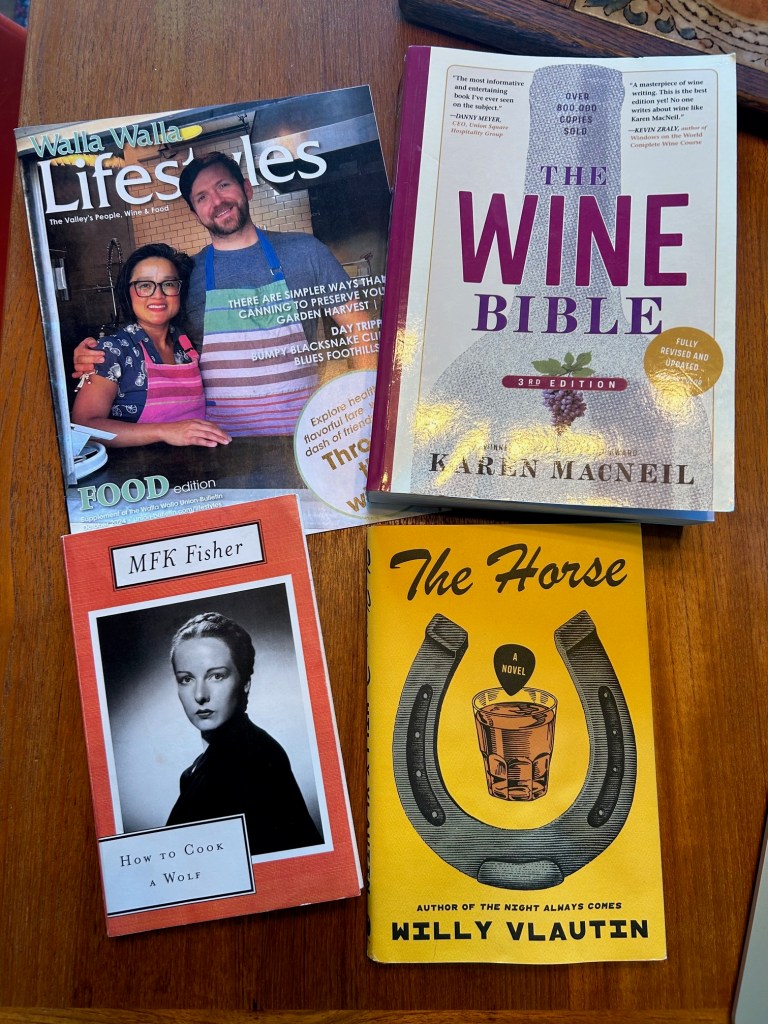

I’ve resumed freelancing for the Union-Bulletin’s Lifestyles magazine (I shot that cover image above on my iPhone) and recently wrote a piece about the new vegan walk-up window in Walawála Plaza, offering residents a lighter, healthier alternative to the fast food and heavy fare easily found in town.

Among other soon-to-be-published stories on Visit Walla Walla, I scribbled up this post about the new (and amazing-smelling) “witch shop” and apothecary on Colville street.

On my nightstand, I’ve been making my way through “How to Cook a Wolf,” by MFK Fisher; “The Horse,” by Willy Vlautin; and the recently revised issue of Karen MacNeil’s “The Wine Bible” (I used to consult the first edition occasionally for reference, but as I’ve been giving the topic of wine writing in general more consideration these days, I’m paying a lot more attention to how wine is written about, and who’s doing the writing). So, I’m now reading the Bible chapter by chapter, which is a good refresher on the basics of wine and winemaking, and often, quite illuminating on aspects I’ve never considered.

For example, MacNeil often presents little facts about wine that are mysteries, like a wine’s finish: “…no one knows why certain wines possess a long finish. Is it a vineyard characteristic? Something about certain vintages? A quality associated with certain physiological states like ripeness? There is no definitive answer.”

Likewise with tannins, “intellectually intriguing compounds…not yet well understood by researchers. I have read studies where otherwise staid scientists refer to tannins as a ‘freaking nightmare’ and to the processes by which it operates as ‘a chemical train wreck.’”

To me, it’s reassuring that even the experts don’t know everything about wine, and that the accepted language used to describe and characterize it—such as tannins, and a wine’s length—isn’t even fully understood!

It’s also curious: What does it mean when we write and speak about wine (or any subject, really) using words that aren’t definitive or fully understood? What is being communicated, or can be communicated, when the words used to describe the subject lack a common meaning?

Airport District

A similar idea was explored by writer Kate Dingwall in an article in Wine Enthusiast, “A New Generation of Sommeliers Is Rewriting the Language of Wine.”

“Part of the issue surrounding language is that it is deliberately difficult for most people to understand. When prohibition ended in the United States, and producers were struggling to get back on their feet, American marketers positioned wine as a symbol of prosperity and aspiration. ‘Wine quickly became something for the white elite,’ [Wine Linguist Alice] Achayo says.”

It is appealing to me to think about how to invite and welcome more readers into the world of wine for two reasons.

- 1: The wine economy is struggling, as I wrote in my inaugural post, and for basic survival—not to mention growth, if that’s even possible—wine lovers and the wine-curious must be met where they are, with language (from that which is used in writing and publications, to guest interactions at the tasting room) that’s inviting and encouraging of curiosity. If the rules and language of wine happen to be the main barrier to discovering it, shouldn’t the rules and language be thought of differently?

- 2. As a wine-loving, plant-based eater who has often felt excluded from the wine world, it sucks feeling unseen and unwelcome when all you want to do is taste new, interesting, or delicious wine, and most wine-tasting + food pairing events are meat-centric and clearly do not care that you exist. Having personally experienced this sort of discrimination in the wine world over and over, I have grown incredulous at the lack of creativity and obliviousness the wine world has shown about the plant-based diet (which has slowly simmered into my own personal crusade to help usher in a new way of thinking about food and wine…trust me, more on this is forthcoming), and it’s become blatantly obvious to me that the industry is in desperate need of a new paradigm.

I mean, if vegetarians like me, not to mention a new generation of sommeliers, are feeling left out from wine, what other groups have felt excluded?

Poor people and the resource-constrained would be another—there’s a reason why beer and whiskey (not wine) always feature prominently among Vlautin’s down-on-their-luck characters. Yet, as Fisher writes in her 1942 treatise on how to live as well and wisely as possible when “the wolf is at the door,” even in times of cash or food insecurity, wine, beer, aperitifs, or a cocktail should be enjoyed—if available.

“If your sherry merchant is honest about the sherry he will probably be honest about other wines as well, and you should with impunity be able to fill a gallon jug for little more than a dollar with good characterful red or white wine, not notable but not infamous. [This is possible only if you know the vintner and can go to his cellar, jug in hand. But there are several reputable blended table wines available now, for about three dollars a gallon. They make an occasional ceremonial bottle of fine wine taste even finer.] It should be the kind that makes your food taste better, and leaves a nice clean budding on your tongue, and makes the next morning seem fortunate rather than a catastrophe.”

Fisher understands perhaps the most universally understood concept about wine—it is for everyone. That certain people and groups don’t feel that way is unfortunate, but in this there is a huge opportunity, if the wine business doesn’t get in its own way.

Leave a comment